–Why recent stakeholder capitalism statement isn’t very radical

–Why Milton Friedman would mostly approve

–Cliff Asness partial defence of imperfect shareholder value (cf. James Montier on world’s dumbest idea)

–How pie growing strategies are good for all stakeholders

–The importance of extra-financial capitals, such as Tyler Cowen’s weighting to the environment

–Why intersubjective myths and innovation are important.

Much fanfare is being made of a recent announcement by a group of CEOs about looking after more “stakeholders” than simply shareholders. A stakeholder capitalism. This idea is very old.

As written I don’t think it’s much more different from the flavour of capitalism we have been dealing with for a few decades (perhaps a touch less than some aspects of extreme neo-liberalism). It’s not the radical re-imagining that the populist left or right are hinting at.

Take the Credo as laid out by healthcare company, Johnson and Johnson:

We believe our first responsibility is to the patients, doctors and nurses, to mothers and fathers and all others who use our products and services. In meeting their needs everything we do must be of high quality. We must constantly strive to provide value, reduce our costs and maintain reasonable prices. Customers' orders must be serviced promptly and accurately. Our business partners must have an opportunity to make a fair profit.

We are responsible to our employees who work with us throughout the world. We must provide an inclusive work environment where each person must be considered as an individual. We must respect their diversity and dignity and recognize their merit. They must have a sense of security, fulfillment and purpose in their jobs. Compensation must be fair and adequate and working conditions clean, orderly and safe. We must support the health and well-being of our employees and help them fulfill their family and other personal responsibilities. Employees must feel free to make suggestions and complaints. There must be equal opportunity for employment, development and advancement for those qualified. We must provide highly capable leaders and their actions must be just and ethical.

We are responsible to the communities in which we live and work and to the world community as well. We must help people be healthier by supporting better access and care in more places around the world. We must be good citizens — support good works and charities, better health and education, and bear our fair share of taxes. We must maintain in good order the property we are privileged to use, protecting the environment and natural resources.

Our final responsibility is to our stockholders. Business must make a sound profit. We must experiment with new ideas. Research must be carried on, innovative programs developed, investments made for the future and mistakes paid for. New equipment must be purchased, new facilities provided and new products launched. Reserves must be created to provide for adverse times. When we operate according to these principles, the stockholders should realize a fair return.

Yet this is not that far away from what Friedman - one of the most prominent free market thinkers - wrote in his famous 1970 NYT op-Ed essay and points he makes in Freedom and Capitalism (link end).

Friedman writes:

“...it may well be in the long-run interest of a corporation that is a major employer in a small community to devote resources to providing amenities to that community or to improving its government. That may make it easier to attract desirable employees, it may reduce the wage bill or lessen losses from pilferage and sabotage or have other worthwhile effects….”

Milton Friedman would promote activity that leads to corporate profits – eg investing in employees, customer service, supply chain etc. as a route to profits.

It turns out at the same time I was having this thought, Chicago finance professor, Luigi Zingales was having a similar thought (his washington op-ed end), although more critical as move of “corporate capture” / marketing.

As long time readers will know, I support the idea (or as I’m starting to call it more often the intersubjective myth cf. Harari) of growing “extra-financial” forms of capital – such as human capital, social, relationship, intellectual and environmental (some times falling under the heading of ESG = Environment Social Governance).

But oft times overlooked is Friedman’s critique on the trade-offs of those capitals – but echoed by AQR’s Cliff Asness (quantitative investor (very successful), typically free market advocate) critique – is that the trade-offs between stakeholders eg employees vs customers vs suppliers vs environmental is difficult.

(Asness takes a good swipe at James Montier now of GMO, who writes in an entertaining piece about Shareholder Value as being a dumb idea - see links end. Montier end up advocating for a form of stakeholder view - in that concentrate on the customer and shareholder value will follow - but one can argue that is a shareholder value maximisation strategy as you can only reach shareholder value by an oblique fashion in any case - cf. John Kay)

On twitter, Asness makes a comment that “woke sells” (eg in the case of Nike, it really does).

Under this model (Long-term) profits or perhaps long-term share prices are a market way of discovering, incentivizing or elucidating those trade offs. Share price - in particular short term share price - has been criticised for a long time as not being a proxy for “long term value creation” - this straddles Lyn Stout’s critique in this (although Stout adds in legal philosophy about if a US Corp is a “legal person” and thus not owned by shareholders - I’m not convinced by this argument as owning 51% of a company pretty much does allow you to direct a company how you wish - though in atomised ownership a lot is delegated to directors and management).

Zingales himself examines this question with a paper suggestive of maximizing shareholder welfare over market value.

How do you trade-off between employees and suppliers? If you paid both or either to maximise their value, there would be no business. Same for maximising customer value. Also (and Stout recognises this), employees are also shareholders and customers etc.

The ideas that B-corp has around this are a touch more radical approach. They measure impacts across other stakeholder domains. But in the end they still simply give a certain amount of points to certain actions (eg subsidised childcare =0.7 points) and then add them up - over 80 points = B-corps certified.

Other academics, such as LBS’ Prof. Alex Edmans advocates and demonstrates that “pie growing” strategies are still excellent strategies for growing all stakeholder wealth (perhaps environmental capital is left out of this notion) although there are imperfections (see end for lecture series).

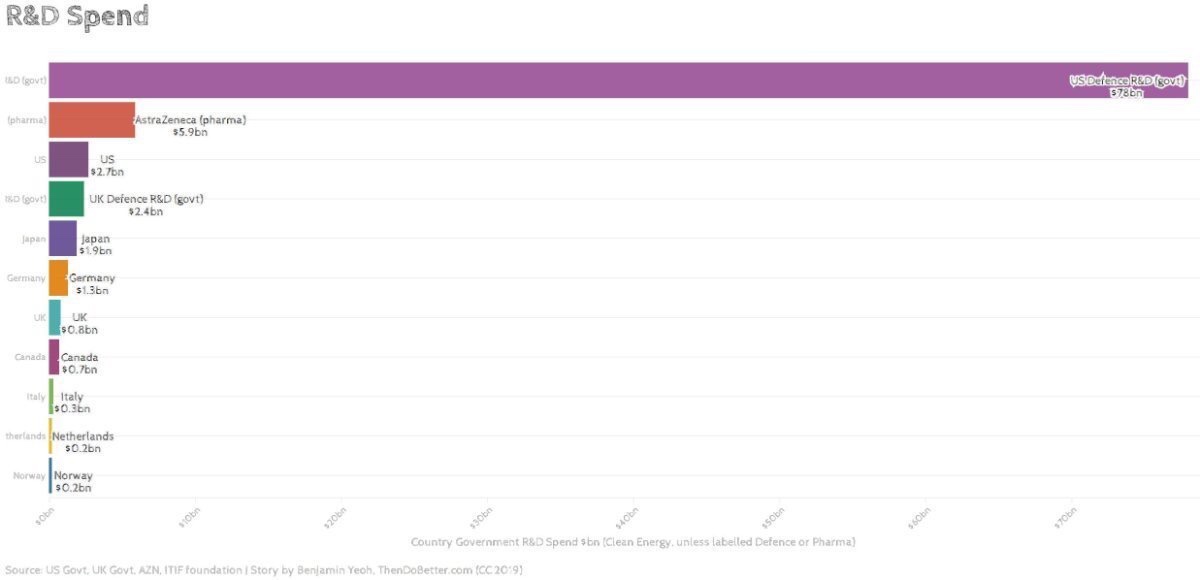

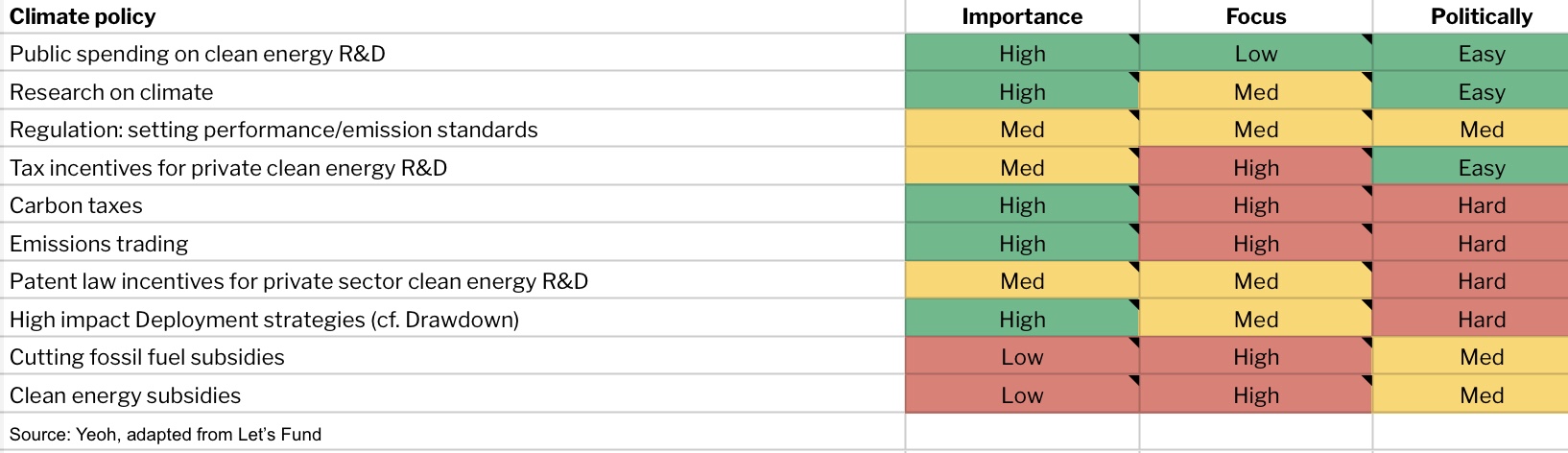

Still the business round table statement as actually expressed is uncontroversial and is not – in my view – a very different flavor of capitalism. The statement also is tangential on environmental capital (via communities the statement “protects the environment”, which was one of the important long-term points made by Tyler Cowen in his philosophical treatise: Stubborn Attachments. Thus the externality / tragedy of the commons problem is potentially unresolved.

I quote the statement:

“…While each of our individual companies serves its own corporate purpose, we share a fundamental commitment to all of our stakeholders.

We commit to:

- Delivering value to our customers. We will further the tradition of American companies leading the way in meeting or exceeding customer expectations.

- Investing in our employees. This starts with compensating them fairly and providing important benefits. It also includes supporting them through training and education that help develop new skills for a rapidly changing world. We foster diversity and inclusion, dignity and respect.

- Dealing fairly and ethically with our suppliers. We are dedicated to serving as good partners to the other companies, large and small, that help us meet our missions.

- Supporting the communities in which we work. We respect the people in our communities and protect the environment by embracing sustainable practices across our businesses.

- Generating long-term value for shareholders, who provide the capital that allows companies to invest, grow and innovate. We are committed to transparency and effective engagement with shareholders.

Each of our stakeholders is essential. We commit to deliver value to all of them, for the future success of our companies, our communities and our country.”

The reflection I’ve picked up from thinkers on capitalism about 200 years ago is how the design of markets was thought to try and keep humans away from more damaging impulses.

Albert Hirschman investigates this in his eloquent treatise “The Passions and the Interests”.

The case is made that capitalism would activate benign human actions at the expense of malignant ones.

Nobel Laureate, and developmental economist, Amryta Sen makes the analogy:

“The basic idea is one of compelling simplicity. To use an analogy (in a classic Hollywood form), consider a situation in which you are being chased by murderous bigots who passionately dislike something about you—the color of your skin, the look of your nose, the nature of your faith, or whatever. As they zero in on you, you throw some money around as you flee, and each of them gets down to the serious business of individually collecting the notes. As you escape, you may be impressed by your own good luck that the thugs have such benign self-interest, but the universalizing theorist would also note that this is only an example—a crude example—of the general phenomenon of violent passion being subdued by innocuous interest in acquiring wealth. The applause is for capitalism as seen by its pioneering defenders….”

Putting this together, leads me to reflect perhaps as many thinkers have suggested we need a better measurement of “wealth” which is beyond GDP. And beyond short-term profits / share prices. But long-run value creation as imperfectly measured by share prices, does capture imperfectly, trade-offs between stakeholders - and most business managers understand that - to increase long run share prices managers eg. invent new useful products for people that takes engaged employees spending time and money in research.

Still moving beyond long-run GDP and long run stock would be helpful if we can add other dimensions of wealth successfully. Again Cowen and others have been suggesting this for a while and there are thinkers working on, for instance, natural capital value. Freedom to work and not be subject to slavery is another form of “wealth” captured elsewhere in our society. (I reflect that historic progressives thought children had a right to work.)

However thinking about the value of other capitals and assets. It’s a hard problem. As I reflected on my journey through the Indonesia jungle – what price running water? What price our rain forests ?

As alluded to in Ray Dalio’s critique of our current late capitalism (and socialism) is that socialism is not very good at growing the pie it seems, but Dalio would argue capitalism is not very good at splitting the pie.

I don’t have an answer to that. (No surprises as if I did, I should be doing some thing very much different with my life). But I have two factors to throw into the mix.

First, it’s the power of stories and our cultural myth narratives. These have the power to dramatically alter our value of different capitals / assets / liabilities. I have mentioned several items on this. I am particularly fond of the examples of how the British banned slavery and on the colour pink (it was not so emphatically a girl’s colour until relatively recently).

Slaves have enormous economic/financial value (and slave-owners were paid off in the battle to ban slavery) but the changing cultural narrative put a heavy “discount” on that value.

If you look back to the code of Harumbi – the ancient law code

“The Code of Hammurabi is a well-preserved Babylonian code of law of ancient Mesopotamia, dated back to about 1754 BC. It is one of the oldest deciphered writings of significant length in the world.”

The Code explicitly values the lives of different types of humans (slaves, non-slaves, elite) in different amounts of silver and different punishments for the different classes. And there are official and unofficial codes today that do similar valuations. For instance, the recent ability for women to drive in Saudi Arabia or permission for marriage etc.

These codes are currently being fought in culture and identity wars. In history, these would have been fought with obvious killing weapons and empires. Today, the weapons are more varied and include cyber and social media warfare. The rules of engagement are less clear.

Second, is the optionality of “innovation” combined with the power of free individuals. The world can be more free, and there can be more innovation. That combination could be unexpectedly great.

These are two items I discuss in my performance-show Thinking Bigly and I am still dwelling on. If you are in London – Do come 13 / 14 November.

Details on Thinking Bigly: https://www.thendobetter.com/thinking-bigly

Zingales on shareholder welfare:

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3004794

his Washington Post op-ed.

Cliff Asness defence: on shareholder value being imperfect but actually still very good

https://www.aqr.com/Insights/Perspectives/Shareholder-Value-Is-Undervalued

In reply to: James Montier who cuts some interesting data on SVM being a dumb idea - file here.

Alex Edmans on pie growing strategies and business in society: Gresham Lectures.

(Really recommended) The Passions and the Interests: Political Arguments for Capitalism before Its Triumph (Hirschman): https://amzn.to/2ZjATuO

Me on Tyler Cowen: Stubborn Attachments

https://www.thendobetter.com/investing/2018/11/21/tyler-cowen-vision-of-free-prosperous-and-responsible-individuals

Dalio on Reforming Capitalism

https://www.thendobetter.com/investing/2019/4/6/ray-dalio-on-reforming-capitalism

Taleb on Dalio

https://www.thendobetter.com/investing/2019/5/17/taleb-on-dalio-capitalism-not-broken-its-skin-in-the-game

Milton Friedman: Do read on Capitalism and Freedom, and his NYT 1970 op-ed is at end too - file here.