Jeff Weiner, Linkedin CEO: “The five deadly sins of "big" companies: Lack of accountability, overspecialization/declining productivity, risk aversion/complacency, lack of context/clear communication, diluting the culture. Good news is that each is highly tractable, especially when addressed proactively. Bad news is that most large orgs are faced with solving all simultaneously, which materially increases the degree of difficulty.”

Japan Value Creation, Corporate Culture, listening to a Prof and CFO

I’ve read Prof. Ryohei Yanagi’s book on the problems of Japanese corporates and value creation. There are specific problems because of the low return on equity and the high cash balances (and entrenched governance). These decisions by many Japanese managements are rooted in the country’s culture and history post-war and a herd mentality. The model (pictured above) is Ryo’s reconciliation of intangible capitals (non-financial/extra-financial/ESG) and market values.

Listening to Ryo talk the full weight of the history and culture aspects comes through. The intersection with religion even becomes apparent. Ryo points out that Japan has a history of Shinto-ism. This places the idea of spirits and gods in the water, in the forests - this gives Japanese a deeply rooted respect for the environment, which is different to other countries in the West.

The animated film, Princess Mononoke, or Spirited Away, gives a sense of this. The films by Ghibli are worth noting. (I have a soft spot for Kiki’s Delivery Service)

Thus in many ways the “E” in ESG-speak for Environment (Social Governance) fits naturally into Japanese corporate philosophies and its peoples’ way of life.

I observe this in the bathing etiquette and shoe etiquette in Japan.

On the other hand, Japan has deep hierarchy (and patriarchy) roots and a long tradition of life-time careers. So while social capital is valued, it is constricted. Hence the male dominance, the age dominance, the corporate layer hierachies which you can find roots in, going back 2,000 years.

Part of this manifests in an impulse to act through “fear of shame” rather than wanting to stand out as a “tall poppy”.

If you believe this contention then you can see how an “Index of honour” perhaps an “ESG index” or a “Blossom Index” (an actual index constructed with gender and ESG indicators, link below) might work to drive a policy of social change or corporate culture change. Critics could argue that this is “virtue signalling”. This is a criticism only if the signal is empty of impact and genuine intent.

For Japanese policy makers increasing female workforce participation and increasing return on capital and productive use of cash and capital are vital to enhance productivity (and generate tax) and combat the costs of an ageing population.

Another aspect that comes to light is alignment with management and shareholders. Management teams in Japan typically own little stock (and employees own little stock) so the stock price tends to matter less. Perhaps, you can argue this matters little if employees have safe jobs and society is served. But, when management teams become only accountable to themselves then the second order problems become apparent. Employees and management are no longer “long-term owners or stewards”.

Is long-term stock price the only measure of value creation? Is it even a complete measure?

The same can be said of a nation’s GDP? It is an incomplete measure of a nation’s wealth.

This brings me to another relatively seldom discussed aspect of corporates. Do companies have a clear sense of purpose? Is this important? An academic, like Prof Alex Edmans (full disclosure he sits on my RLAM Committee) might argue a strong company purpose fulfilled well then goes on to achieve society benefit, stock holder benefit, employee benefit etc. (link below)

One notable aspect of Eisai, the company where Prof Yanagi is currently CFO (again bucking the trend in Japan, Ryo has had several jobs - arguably this has grown his expertise and also allowed it to be shared; although it’s likely been at the expense of his pension...) is that it’s corporate purpose was enshrined in its articles of association.

So, if a New York hedge fund girl wanted to argue with that, it could or would have to start an open proxy battle. Effectively it’s been made a “say on purpose”, an idea that The Purposeful Company (that Alex Edmans is part of, and I’ve had discussions with) have also suggested.

Turning back to Japan, it’s challenges are rooted in its history and culture reflected in the actions and governance of its corporates. The challenges have a different tone to the ones in eg the UK or US. But, as I reflect on this week/month/year/40 years it occurs to me that certain underlying elements remain similar. For instance, not understanding the influence of Christianity in the US, or the worries of ordinary British Brexiteers over “English Culture” leads to as incomplete a picture of the conflicting views in the US and UK, as not understanding Japanese history would lead you as to an incomplete causes of the cash on Japanese corporate balance sheets.

Links:

Previous Short blog on Yanagi’s book: https://www.thendobetter.com/investing/2018/6/20/the-dawning-of-japanese-corporate-governance

The thinking intersects with the Westlake/Haskel book on Intangibles -

https://www.thendobetter.com/investing/2017/11/14/the-rise-of-intangibles-capitalism-without-capital

97% for Kiki and Spirited Away on Rotten Tomatoes

https://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/kikis_delivery_service/

https://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/spirited_away

Japanese Shoe etiquette

https://www.japan-guide.com/e/e2001.html

Info on Blossom Index

https://www.ftse.com/products/indices/blossom-japan

Purposeful Company Work

http://www.biginnovationcentre.com/purposeful-company

The current Arts blog, cross-over, the current Investing blog. Cross fertilise, some thoughts on autism. Discover what the last arts/business mingle was all about (sign up for invites to the next event in the list below).

My Op-Ed in the Financial Times (My Financial Times opinion article) about asking long-term questions surrounding sustainability and ESG.

Current highlights:

A thought on how to die well and Mortality

Some writing tips and thoughts from Zadie Smith

How to live a life, well lived. Thoughts from a dying man. On play and playing games.

A provoking read on how to raise a feminist child.

Some popular posts: the commencement address; by NassimTaleb (Black Swan author, risk management philosopher), Neil Gaiman on making wonderful, fabulous, brilliant mistakes; JK Rowling on the benefits of failure. Charlie Munger on always inverting; Sheryl Sandberg on grief, resilience and gratitude.

Buy my play, Yellow Gentlemen, (amazon link) - all profits to charity

Tyler Cowen: Vision of free, prosperous and responsible individuals

Tyler Cowen has written a moral philosophical treatise that favours sustainable economic growth as the major tool for enriching humanity, but contained by (1) strong forms of human rights and (2) a heavy weighting to the distant future and (3) a wider definition of wealth than GDP which therefore puts much more weight on managing the environment plus the government investing in ideas and other intangible capital for the long-term.

I summarise what a few of the ideas mean to me. My friends will know a lens of the long-term, art/theatre, intangible capital, sustainability, mortality and healthcare, and forms of happiness have been topics of interest to me.

I found it a thoughtful counterpoint to “de-growth” economic philosophers, such as Kate Raworth. Raworth puts much more emphasis on the limits of environmental capital and therefore “circular economy”. Cowan has good regard for the environment but puts weight on economic growth as being the major driver lifting humanity’s wealth-plus over many years of history. I think the interested reader should attempt both sets of work to understand the different lens they come from. Although, my reading of the works suggest much practical overlap even if Raworth refutes “growth” and Cowan claims “growth” as the major driver of humanity. The protection of environmental capital is an overlap, as is protecting future generations, as is a criticism of current GDP measures as a proper measure of wealth.

I like Cowan’s approach of plurality (there are many type of thing that makes us “happy” not one type of thing - the ancient greeks had a few types of love and a few types of happiness, but my reflection is that there are probably even more) and the way important ideas or conclusions cut across traditional lines of left/right thinking. However, if you’ve already dismissed “trickle down” economics and dislike several libertarian notions you’ll likely disfavour certain of Cowan’s conclusions.

Other ideas that spill out is this focus on ideas. This chimes with the work on intangibles I am interested (cf. Haskel & Westlake, Capitalism without Capital) and the very heavy focus of my day job investing work on ESG/intangibles/Sustainability as well as a focus on long-term investing. (see links end)

Cowan ends up on the same page as Nassim Taleb with respect to climate change (I think) because of the emphasis on distant future and weighting future generations heavily. Taleb arrives there via precautionary principle applied to complex system of only one planet. (see links end)

Cowan emphasises not “sweating the little things” and putting a focus on the big material changes. This chimes with the maxims of many investors that boil down investing work to a few small number of important drivers and not a host of detail. Small items (butterfly wings causing a hurricane) can have large impacts but it’s too difficult to predict to sweat them too much. (cf. consequentialist thinking)

Cowan’s focus on the distant future has some regard to restitution for the past. Cowan ends up suggesting restitution with a small premium is a viable solution. This is an interesting outcome to me, especially with respect to climate change and slavery. Perhaps it would argue for a little bit more restitution for black Americans today (as potentially argued by Ta-Nehisi Coates and others) and also that advanced world countries (mainly the US as the major polluter historically) should be doing more to balance their large historic levels of pollution. I’m unsure that conclusion though will have much majority buy-in with the American people - but as a form of restorative justice, I think it could resonate well with historically oppressed minorities and level 1 / 2 countries (cf Rosling definitions).

Cowan has less weight on (the enormous expense) of caring for the last years of the elderly at the expense of the young. I think this is interesting as it chimes with some practical thinkers on healthcare. (It chimes with with science fiction work. Cowan seems struck by imaginative Sci Fi challenges). I’m particularly thinking of Atul Gawande’s book - On Mortality (see link end) but also the health economic work suggesting enormous cost in the last 6 to 12 months of life and of limited quality of life / life extension benefits. This would be better spent on other investment (the young or simply long-term ideas generation). One almost-irony being that when terminally ill choose positive palliative care, they often live longer than groups who opt for medicalised treatment to the very end - “we live longer when stop trying to live longer”. This gives a moral frame work for a thorny practical problem.

Cowan has some weight on faith. In some ways, one has to, if one puts weight on the distant future. That is an act of faith.

OK… on to some details:

Right/Wrong are typically absolute. Humans are very prone to error - irrational minds. We need to be fortified against self-deception.

“What’s good about human life can’t be boiled down to any single value” this plural view, I liked a lot. It resonated with what I understand through my life - I’m a husband, father, son - I’m a playwright - some time artist - reader - writer - long-term investor - cook and food lover. I don’t practise much sport or gym but I’ve cried thinking about my father while listening to Europe re-claim the Ryder cup, I’ve cheered and commiserated with my mother while watching Liverpool football club, I’ve sat through a 5 day cricket test match like a long Shakespeare play.

This messiness is important and I find Cowan partially reconciles this. Cowan reconciles much with a “common sense morality” which I observe most people typically apply in practice.

“We need to make room for beauty and justice” and mercy and kindness and art and …. I find too often economists can not make room for these notions whereas I observe humans spend much time on them.

And so, Cowan suggests:

“

First, I do not take the productive powers of economies for granted. Production could be much greater than it is today, and our lives could be more splendid. Or, if we make some big mistakes, production could be much lower, and we could all be much poorer.

…

Second, I will seek to revise some of our intuitive assumptions about moral distance. Which individuals should exert more of an influence over our choices, and which should exert less? I will argue, for instance, that the individuals who will live in the future should be less distant from us, in moral terms, than many people currently believe. Their interests should hold greater sway over our calculations, and that means we should invest more in the future. Even though it is sometimes hard for us to imagine how our actions will affect future people, especially those from the more distant future, their moral import remains high. I will therefore be asking humans to have greater faith in the future….”

I’ve realised this blog is going on, so I’m going to for now briefly skimp the 6 areas of debate Cowan covers:

Time - weighting the future/past

Aggregation - weighing one individual’s choice over another

Rules - Cowan speaks up for rules

Rights - Cowan speaks up for rights

Radical Uncertainty - how to make better choices under uncertainty

Common sense morality - work hard, take care of our families, live virtuous lives but helping other periodically where we are able to (with exceptions for the Martin Luther King’s of this world…)

To hit two major thoughts:

(I) the productive powers of the economy

(II) the weighting of “moral distance” of future generations to us

and I hope to come back to some of his other problems in another blog.

so on (i) Cowan advocates that governments / society should maximise the long run rate of wealth/economic growth and that it should be measured by “wealth plus”

Wealth plus is GDP plus measures of leisure time, household production and environmental amenities.

“Wealth Plus : The total amount of value produced over a certain time period. This includes the traditional measures of economic value found in GDP statistics, but also includes measures of leisure time, household production, and environmental amenities, as summed up in a relevant measure of wealth. In this context, maximizing Wealth Plus does not mean that everyone should work as much as possible. A fourteen-hour work day might maximize measured GDP in the short run, but it would be less propitious over time once we take into account the value of leisure, not to mention the potential for burnout. Still, this standard is going to value a strong work ethic. 1 Maximizing Wealth Plus also does not mean destroying the natural environment. It’s now well understood that environmental problems can lower or destroy economic growth through feedback effects. We should therefore protect the environment enough to preserve and indeed extend economic growth into the more distant future. More broadly, the principle of Wealth Plus holds that we should maintain higher growth over time, and not just for a single year or for some other, shorter period of time.”

My particular concern here is that wealth plus is still too narrow a definition and fails to encompass certain notions of humanity he refers to elsewhere.

I can accept maximising wealth plus especially with a view to the distant future can increase human prosperity and happiness, but I wonder on the many intangible items that are hard to measure (not all things that count, are countable) that are left out - art, dance, community - all the “social and human” capitals - perhaps that is partly captured by the idea of “leisure” time but even in our financially poorest communities there is dance and song and art - and those items have value.

Perhaps the concept of “capital” is simply a poor notion for them. Linguistically and culturally come places shy away from the idea of human capital as it too closely evokes notions such as forced work labour camps.

I also wonder about causality here. There is the argument of Milton Friedman to seek corporate profits (and social goods spill out of that) but that’s potentially evolving into a wider stakeholder model that corporate profits spill out of fulfilling human wants and needs - that profits or wealth is an effect of labour/capital/resources/ideas and that the total wealth mix of a nation mix contains much “other capital” not quite captured in the wealth plus definition.

Still the wealth plus definition does raise three questions that cut across political lines:

He summarises;

“We can already see that three key questions should be elevated in their political and philosophical importance, namely:

What can we do to boost the rate of economic growth ?

What can we do to make our civilization more stable ?

How should we deal with environmental problems ?”

One last thought before moving on. Cowen argues for policies that do not pursue immediate growth too vigorously. He cites the Shah of Iran trying to modernise Iran too fast and arguably causing more damage that a more cautious approach.

I’m intrigued by this incrementalist view. It chimes with several observations I have. I wonder if you can see brexit through this lens. Brexit seems now to be a fairly radical break and the schisms it is throwing up are not incremental.

It also may not apply so readily on the company level. Companies may need more radical action to return to growth or become irrelevant. However, macro level policies may do better building on what that country has already built up. Will dwell on it more.

Also, cf. Amryta Sen’s work.

Conclusion, has thrown up lots of ideas. Worth a read if you’d like to be challenged by a short read on a moral philosophy that ends up advocating for the environment, for growth, for sustainability and for thinking more about future generations.

As a counterpoint on trickle down economics read: try this from some IMF economists https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/sdn/2015/sdn1513.pdf

If this has gone too deep, try (a centre-left view) 23 Things They Don't Tell You About Capitalism

by Ha-Joon Chang Amazon link here https://amzn.to/2zoSbwe

On intangibles see: https://www.thendobetter.com/investing/2017/11/14/the-rise-of-intangibles-capitalism-without-capital

Nassim Taleb on climate here: https://www.thendobetter.com/investing/2017/9/18/nassim-taleb-climate-change-risk

Atul Gawande On Mortality: https://www.thendobetter.com/blog/2018/8/16/mortality-how-to-die-well

Cowen’s book - Amazon link here.

UK Poverty, severe and worse if there's a disabled person in family

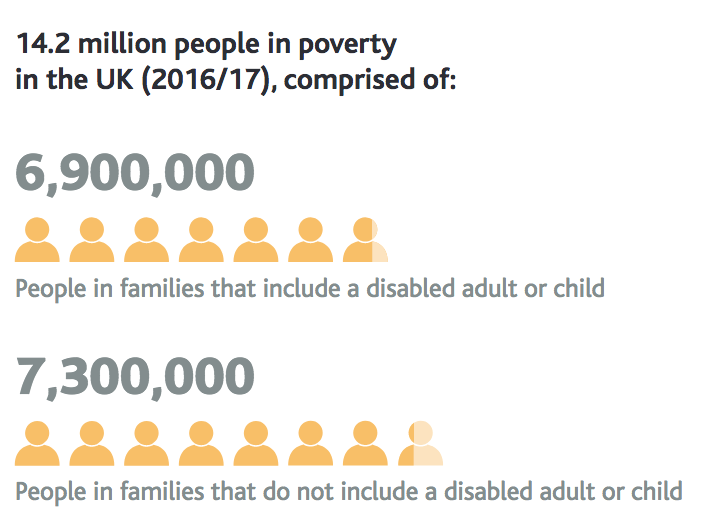

14.2 million people in poverty in the UK, 6.9 million (48.3%) are living in families with a disabled person. Given that only 35% of families in the UK have someone with a disability, this shows that families with someone with a disability are significantly over- represented within the population in poverty. Poverty rates also vary across people in families with different disability statuses. The poverty rate for people living in a family with a disabled adult or child stands at 27.6%, whereas for people living in a family where no-one is disabled, the poverty rate is 16.3%.

The SMC measure of poverty suggests that 22.0% of the UK population is living in a family considered to be in poverty. Poverty rates for children are far higher (32.6%) than those for working-age adults (21.6%) and pension-age adults (11.4%). This means that there are 14.2m people in poverty in the UK, comprised of 8.4m working-age adults, 4.5m children and 1.4m adults of pension age.

There has been much debate on poverty measures with no agreed upon UK metrics. The Socail Metrics Commission has taken thinkers (from both left and right) to look at metrics and this seems very robust to me.

The figures are more severe than I would have guessed. I think this might be suggestive of austerity not working well for thos ein poverty although the policy and structural factors are complex. This seems to be view the view of a recent UN inspector visit.

UN prof visit - “Statement on Visit to the United Kingdom, by Professor Philip Alston, United Nations Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights”

Public Sentiment and price of Corporate Sustainability

Recent Prof. George Serafeim paper combining TruValue Labs ESG data (machine learning) with MSCI ESG data (rules based analyst) “combining big data and analyst driven ESG data allows one to identify ‘value’ opportunities in the ESG space and as a result construct an investment strategy that delivers alpha while investing in companies with greatly superior ESG performance scores.” [scores as defined by these data sets] “the price of corporate sustainability performance has increased over time. This is the estimated premium (if positive) or discount (if negative) that firms with better sustainability performance trade relative to peers after accounting for several factors such as current profitability, size, leverage, past returns and other firm characteristics.” “The higher price of corporate sustainability poses a challenge for ESG investors. Do you get a good value for money from your investments? It is not only a matter of the value of corporate sustainability anymore, but it is also a function of the price you are paying for it. Value for price is key.”

H/T George Serafeim (LI link)

Study link: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3265502

“Combining corporate sustainability performance scores based on environmental, social and governance (ESG) data with big data measuring public sentiment about a company’s sustainability performance, I find that the valuation premium paid for companies with strong sustainability performance has increased over time and that the premium is increasing as a function of positive public sentiment momentum. An ESG factor going long on firms with superior or increasing sustainability performance and negative sentiment momentum and short on firms with inferior or decreasing sustainability performance and positive sentiment momentum delivers significant positive alpha. This low sentiment ESG factor is uncorrelated with other factors, such as value, momentum, size, profitability and investment. In contrast, the high sentiment ESG factor delivers insignificant alpha and is strongly negatively correlated with the value factor. The evidence suggests that public sentiment influences investor views about the value of corporate sustainability activities and thereby both the price paid for corporate sustainability and the investment returns of portfolios that consider ESG data.”

Comment: There is still a lot of practioner debate about the value of various ESG datasets and ratings. However, for those who go down a deep fundamental analysis route a variety of data sources is often seen superior than one. This is one of the first papers I have seen that has looked at combined two datasets/ratings that are developed from very different methodologies.

Cycles, economic, market, debt...

Where are we in this up-leg part of this cycle? Two recent books address how investors - and other interested parties - can look at the world and approximately place where we are in a cycle and have a view on what has gone before which impacts what happens now in the future. It chimes with an earlier post on Hyman Minsky, who constructed a model of a cycle that uses human psychology (see link end).

Ray Dalio recently wrote Principles (see links end) and is now giving away a book on his understanding of the debt cycle. Dalio is convincing on why debt cycles will always occur (and like Howard Marks and Minsky) explains the human psychology behind why this might be the case.

Howard Marks, who writes a widely read investment letter for his money management firm, has recently published his work focusing on the economic and market cycle (but touches on the debt and other cycles too - he makes the point that they are inter-related).

Both are very valuable for investors giving practical thoughts on how to assess cycles, but for those simply interested in what are powerful trends and forces that have shown patterns through out human history, it will also give insights into why we have booms and busts - and why we will continue to have them.

Both books are recommended.

As to the state of the world now? Both Dalio and Marks sound notes of caution in recent months. I will note Marks recent Memoo

“I’m absolutely not saying people shouldn’t invest today, or shouldn’t invest in debt. Oaktree’s mantra recently has been, and continues to be, “move forward, but with caution.” The outlook is not so bad, and asset prices are not so high, that one should be in cash or near-cash. The penalty in terms of likely opportunity cost is just too great to justify being out of the markets.

But for me, the import of all the above is that investors should favor strategies, managers and approaches that emphasize limiting losses in declines above ensuring full participation in gains. You simply can’t have it both ways.

Just about everything in the investment world can be done either aggressively or defensively. In my view, market conditions make this a time for caution.”

And

“In memos and presentations over the last 14 months, I’ve made reference to some specific aspects of the investment environment. These have included:

the FAANG companies (Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix and Google/Alphabet), whose stock prices incorporated lofty expectations for future growth;

corporate credit, where the amounts outstanding were increasing, debt ratios were rising, covenants were disappearing, and yield spreads were shrinking;

emerging market debt, where yields were below those on U.S. high yield bonds for only the third time in history;

SoftBank, which was organizing a $100 billion fund for technology investment;

private equity, which was able to raise more capital than at any other time in history; and

cryptocurrencies led by Bitcoin, which appreciated by 1,400% in 2017.

I didn’t cite these things to criticize them or to blow the whistle on something amiss. Rather I did so because phenomena like these tell me the market is being driven by:

optimism,

trust in the future,

faith in investments and investment managers,

a low level of skepticism, and

risk tolerance, not risk aversion.

In short, attributes like these don’t make for a positive climate for returns and safety. Assuming you have the requisite capital and nerve, the big and relatively easy money in investing is made when prices are low, pessimism is widespread and investors are fleeing from risk. The above factors tell me this is not such a time.”

And here’s Dalio on Debt:

“To summarize some of the key points found in the book:

All big debt cycles go through six stages, which I describe and explain how to navigate:.

The Early Part of the Cycle

The Bubble

The Top

The Depression

The Beautiful Deleveraging

Pushing on a String/Normalization

2. Getting the balance right between having too much debt (that causes debt crises) and too little debt (which causes suboptimal development) is never done perfectly. Cycles always swing from having too little debt relative to the opportunities to having too much and back to having too little and back to having too much. These swings are exacerbated because people tend to remember what happened to them more recently rather than what happened a long time ago. As a result, it is pretty much inevitable that the system will face a big debt crisis every 15 years or so.

3. There are two major types of debt crises—deflationary and inflationary—with the inflationary ones typically occurring in countries that have significant debt dominated in foreign currency. The template explains how both types transpire.

4. Most debt crises can be well-managed if 1) the debts denominated in one’s own currency and 2) the policy makers both know how to handle the crisis and have the authority to do so. As I write in the book: “Managing debt crises is all about spreading out the pain of the bad debts, and this can almost always be done well if one’s debts are in one’s own currency. The biggest risks are typically not from the debts themselves, but from the failure of policy makers to do the right things due to a lack of knowledge and/or lack of authority.”

Both Marks and Dalio are billionaires, who have been investing over decades. Their thoughts are worth reading.

Hyman Minksy - "We fat all creatures else to fat us, and we fat ourselves for maggots. " Hamlet, Shakespeare.

Ray Dalio - thoughts on populism. His book on debt available here.

The current Arts blog, cross-over, the current Investing blog. Cross fertilise, some thoughts on autism. Discover what the last arts/business mingle was all about (sign up for invites to the next event in the list below).

My Op-Ed in the Financial Times (My Financial Times opinion article) about asking long-term questions surrounding sustainability and ESG.

Current highlights:

A thought on how to die well and Mortality

Some writing tips and thoughts from Zadie Smith

How to live a life, well lived. Thoughts from a dying man. On play and playing games.

A provoking read on how to raise a feminist child.

Some popular posts: the commencement address; by NassimTaleb (Black Swan author, risk management philosopher), Neil Gaiman on making wonderful, fabulous, brilliant mistakes; JK Rowling on the benefits of failure. Charlie Munger on always inverting; Sheryl Sandberg on grief, resilience and gratitude.

Buy my play, Yellow Gentlemen, (amazon link) - all profits to charity

Why ESG ratings will never agree and some of the problems of ratings

Source: WSJ

Tesla vs Exxon? ESG ratings are like stock opinion reports more than fact. WSJ article unpicks methodology and score of 5 major companies and higlights the wide dispersion of results and different methodologies. (Summary outcomes above)

Like a stock report, you should understand the assumptions and methods to derive “Buy/Sell/Target Price” when utilising analysis. An investment analyst rating is an opinion, so is an ESG rating. The WSJ piece dissects why the ratings are so different. The components of methodology and weighting.

“The problem here isn’t the ESG ratings, but that they are used as though they were some sort of objective truth... they are no more than a series of judgments by the scoring companies...and investors who blindly follow their scores are buying into those opinions, mostly without even knowing what they are.”

“Investors should not treat ESG scores as settled facts to be used on their own, but as potentially worthwhile analysis that needs to be understood before being acted on. The thick ESG reports behind the scores offer useful detail about the policies and controversies around each business. But just as with financial accounts, investing without understanding is unlikely to deliver what you want.”

My Linkedin Post is over 10,000 views and 100 likes and counting, with many of the ratings providers (most who I know) providing comments.

From FTSE:

• The comparison to sell side research & buy/sell ratings is an interesting one. It should be valid but in reality the high correlation & herding that you see in sell side ratings is actually not seen in ESG ratings – as shown in the article.

• As far as I’m aware, no one in the ESG data / ratings market is claiming to provide some form of objective truth. All outputs are based on methodologies and as the article points out – it’s essential to consider how scores and ratings are derived and that as an end investor / user you are comfortable with this.

• For example, at FTSE we have always maintained separate datasets for assessing how a company operates (our ESG Ratings) and the products and services that companies manufacture / provide (our Green Revenues data). We have found that investors appreciate this distinction. Just because a company is contributing to the green economy does not mean that it is doing a good job of managing a range of operational ESG issues…Attempting to net these things off in a single number is problematic.

• Generally speaking, at FTSE we aim to be as transparent as possible – in particular with the issuers we rate e.g. in addition to sharing all of our data with each company in our universe as part of our annual research cycle we now provide (for free) a “Corporate Peer Comparison Tool” which allows companies to see both the scores & ratings (including for Green Revenues) that we have derived as well as comparison to their peers by sub sector, industry, country etc.

From Xi Li (of Active Ownership paper fame):

“Academics have criticized these ESG ratings for a long time.... not surprising. A better way to use these ratings is to compare it in a time-series manner (i.e. Tesla's rating last year vs. current year), not cross-sectionally (i.e. Tesla vs Exxon). However, even this may have problems, because these data providers' algorithm may change over time... “

From Mike Tyrell (of SRI-Connect)

It would indeed be an encouraging evolution if both suppliers and users of ratings came to regard them as opinions rather than in any respect as objective reality. However, I fear that we are still some distance from a situation in which asset managers buy / sell / focus on / ignore a stock bsed in a rating from one provider are treated with the same derision as they would be if they bought / sold a stock based on the recommendation from a single broker. ... and we should note that James Mackintosh's main concern seems not to be the fundamental active managers who can pick and choose ratings and research but the "billions of dollars of exchange-traded funds based on ESG indexes ... [and] ... fund managers [who] are being pushed to produce portfolios with better ESG ratings, encouraged by public mutual-fund ESG scores." There is, it seems to me, a real problem with the same research processes being used to produce pre-trade investment advice (counter-consensus opinion needed) and post-trade portfolio analytics (objective exposure data needed). I can't quite articulate the nature of the problem and I certainly can't see a business model that would fix it ... but I think it's one to watch. … He also comments back to FTSE… Aled Jones - I agree that no-one would openly claim 'objective truth' but I suspect that both sides are guilty of treating opinion as if it were this. There is equally a small number of research firms claiming "this is just the opinion of an analyst"

From Sustainalytics:

…Sustainalytics tries to differentiate itself from its competition by the transparency we provide to our clients. We are not a black box. That said, we don’t provide full methodological details publicly. … but do give more colour on the Tesla rating…Fully agree with your points and many of the points in the article. Sustainalytics agrees that ESG is a separate signal and one that needs to be interpreted alongside other financial information. Also, ESG Ratings and what they measure are not as standardized as traditional financial signals. In regards to Tesla, from our analyst: “Tesla’s management of these issues ranges from one extreme to the other. What it manages well – the carbon impact of its products – it manages very well, while on the other hand, its management of human capital and product governance risks reveals significant shortcomings. As a company committed to the production solely of electric vehicles and other products related to renewable energy, Tesla is the global leader among automakers when it comes to the carbon emissions of its fleet – no small achievement. However, the company has been involved in a steady stream of controversies related to the timely delivery of cars, the safety of its autopilot technology, and its management of its workforce, and despite such controversies, commitments to labour rights and programmes governing product quality are lacking.”

Some quant data looks at some of the ESG ratings sets are here (not peer reviewed): A look at using the Thomson Reuters Data set and by BAML can be found here.

Another lens in a more quant fashion can be found in this MSCI look through its own data and a return on capital lens. And Nordea Quant also look at it through the MSCI lens.

Other papers and thoughts to look at:

Why ESG might be so important in an intangible world

and an academic paper on Active Ownership and why and how it adds value.

Cancer improvement rates, biomedical capital allocation

Source: https://ourworldindata.org/cancer#cancer-survival-rates

Cancer survival rates and cures have enormously improved over the last 40 years. From 5 out of 10, 5 year survival rates to close to 7 out of 10 5 year survival rates (although sadly not for pancreatic).

Much like the Hans Rosling Factfulness book argues, we should acknowledge how much better certain items are despite considerable challenges going forward.

I think there are some hard conversations to be had on the allocation of resources on aspects of innovation, especially towards very end of life care.

This you can sense from Atul Gawande’s book, Mortality (Gawande Mortality blog post ). If someone is facing average survival of 3 to 6 months, and the tail chances of survival of eg. 2 years are extremely low then a balanced conversation is needed.

One parallel to this can be seen in the Biomedical Bubble paper. I have several critiques, which I haven’t the capacity to spell out properly here, but one of the central ideas could be epitomised by the notion of spending $1bn on development a treatment that increases survival, say 6-12 months, and is not a cure vs spending that money on prevention or other system innovations is a mis-allocation of capital. I think that argument has some validity - although the pricing of life and innovation is a tricky area particularly in second order insights and technology from biomedical research (and that plenty of biomedical cost is late stage and undertaken by private companies). Perhaps, that needs more input from philosophers (some of the basis of the UK’s NICE framework of pricing Quality Life Adjusted Years springs from this philosophy work and ideas of distributive justice, as well as the value/costs of road building - see Value of life, under constrained budgets )

Some provoking reads on health innovation in those above/below links.

Blog on Rosling data

Atul Gawande Mortality blog post

Value of life, under constrained budgets - see the work of philosopher Jonathan Wolff on a somewhat accessible look at this.

The current Arts blog, cross-over, the current Investing blog. Cross fertilise, some thoughts on autism. Discover what the last arts/business mingle was all about (sign up for invites to the next event in the list below).

My Op-Ed in the Financial Times (My Financial Times opinion article) about asking long-term questions surrounding sustainability and ESG.

Current highlights:

A thought on how to die well and Mortality

Some writing tips and thoughts from Zadie Smith

How to live a life, well lived. Thoughts from a dying man. On play and playing games.

A provoking read on how to raise a feminist child.

Some popular posts: the commencement address; by NassimTaleb (Black Swan author, risk management philosopher), Neil Gaiman on making wonderful, fabulous, brilliant mistakes; JK Rowling on the benefits of failure. Charlie Munger on always inverting; Sheryl Sandberg on grief, resilience and gratitude.

Buy my play, Yellow Gentlemen, (amazon link) - all profits to charity